|

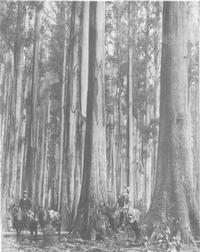

To describe what the forest was like is best left to the first to write about it.

A.R. Selwyn reported in 1856 that near the Mt Dandenong summit he measured a fallen tree that was 216 feet to the first

branch and 18 yards in cicumference at a point 3 or four yards from the ground and commented that there were "many more

of equal dimension".

J.W. Bielby of Glen Fern wrote of the 1850's, "The soil on the summit of the mountain range is rich, supporting huge

blue gum (sic) trees. Cattle made paths by which, with care, a horseman could go. I have measured the circumference of one

of these, which is 16 stirrup leather lengths of 5 feet each, about 80 feet and the height of the stern of one of these lying

prostrate like a huge long wall, 27 ft. high, but though trees have been described as to 300-500 ft. in height, the longest

prostrate size I measured was 295 ft. Though of vast bulk and seemingly by rings cut across, 400 years old. At one site on

the mountaintop 16 large trees were in view all at once, the smallest of the lot being 22 ft. in circumference. This spot

was towards the head of the Monbulk Creek but the largest trees were at the head of the Dandenong Creek, where in the early

50's scrambling over a log, I lost a valuable telescope in a red morocco case from my pocket"

"Even during the 1880's some very big trees remained in the hills. In 1888, Menzies Creek produced a tree said to

be the "Largest In The World" and this was displayed at the Centennial Exibition held that year in Melbourne. The

tree, felled in an area noted for giants, measured 68 feet in girth at the point of ringing and was carted to Melbourne in

sections and re-erected outside the Exhibition buildings. The big ash remained in the Fitzroy Gardens until comparatively

recently. Approximately 40 years ago, Jas. O'Donohue Snr. discovered a "giant tree" measuring 66 ft. in circumference

in the Sherbrooke forest and about the same time another big tree in the valley of the Menzies Creek between the latter town

and Clematis was a drawcard for tourists."

Paling splitters were the first to exploit the enormous straight grained hardwood giants.

"The paling knife and "tommy" were standard equipment for the splitters who cut palings and fence rails

from giant "blackbutts" in the higher forest.

First, the splitter cut his way through the dense undergrowth until he reached a tree with a straight barrel, indicating

that it was likely to split easily. He then tested the tree by "chipping in" with an axe and cutting a piece of

bark which he jerked and peeled from the tree to see that it ran straight to the top.

If satisfied the splitter then took a chip measuring about one foot by nine inches, cut about three inches thick and this

was split and examined for strings. If a test proved satisfactory, the splitter and his mate felled the tree, mostly by means

of a large cross-cut saw operated from a springboard.

The tree was cut into six foot logs, subseqently split into billets measurung six by six and these were stacked ready

for splitting, faulty or knotted billets being discarded. The billets were in turn split into palings with a paling knife,

a special implement consisting of a flat blade set at right angles to a small 15-inch handle. The billet was placed in a brake

(or vice) to hold it steady and was first cut in half and later split into several palings. The splitter held the paling knife

in his left hand and started the split with a "tommy", a club-like piece of blue gum which was used to hammer the

paling knife. He levered the knife and tommy backward and forward to guide the course of the split and it was this operation

which required the skill possessed by so many early bushmen. (Some splitters even dropped the tommy and placed a muscular

right hand and forearm in the crack)

The technique for splitting rails-which measured 2.5 inches on one edge and narrowed to 1 inch on the other-was slightly

different, in that wedges were used to split the timber. Fencing posts were also cut from the forest and were morticed by

means of an auger fitted to a frame.When scantling timber was required, the log was placed on the ground and a line dipped

in boot blacking pulled over it's surface. A splitter with a broad axe then marked the traced line and the log was subsequently

split in accordance with the markings"

In 1878, 10,000 acres of the Dandenong and Woori Yalloak State Forests were thrown open for private sale and the settlers

earned a living while their crops were growing by felling the giant "blackbutts" that were split into palings and

rails and carted to Melbourne.

"Smaller blackwood and silver wattles were cut into staves for tallow casks and the bulbous roots of musk trees were

sawn into slabs and exported to Germany for use in the fashioning of jewellery boxes."

Extracts from The Story Of The Dandenongs by Helen Coulson 1958. See the References page

The Flora

This small parcel of land, of no more than 50 acres contains several different plant communities

There is the mountain ash Wet Forest of the Yanakie slope and the Clematis Creek surrounds and the grey gum/messmate stringybark

Damp Forest of the more northerly aspects of the valley sides plus the exposed shallow gully floor upstream from the bridge

supports pure stands of both blackwood and manna gum while the Nation Rd slope is home to almost exclusively messmates

|